The biggest economic story of the post-pandemic period has been inflation.

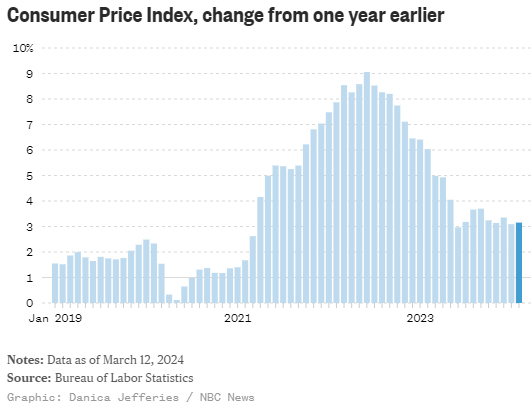

It's a narrative that, at first, had two clear phases. First came the breakneck acceleration in price growth amid reopenings and job changes, when the 12-month inflation rate surged from less than 1% in June 2020 to more than 9% in June 2022.

Then the fever appeared to break, with price growth slowing over the next 12 months to just 3.1% in June 2023.

Yet it is now clear that a third chapter has emerged: a stall. For the past nine months, the annual rate of inflation has held between 3% and 4%.

On Tuesday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the Consumer Price Index climbed 3.2% in the 12-month period ending in February — missing expectations of a slightly lower 3.1% reading, and coming in higher the 3.1% seen in January.

On a month over month basis, prices climbed 0.4% in February compared to 0.3% in January. That was in line with expectations. But the so-called core reading, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, came in at 0.4%, above expectations for a reading of 0.3%.

"Inflation remains unusually high," Jason Furman, a Harvard economics professor and the former White House Council of Economic Advisers chief under President Barack Obama, wrote Tuesday morning on X. He noted core inflation has actually been kicking higher over the past several months when three-month averages are considered.

Experts began warning last year that the so-called last mile of the marathon toward the 2% goal would be the hardest. It now appears those fears have been borne out.

"I think that the market got ahead of itself when it came to how fast we'd get back to 2%," said Michael Antonelli, managing director and market strategist at the financial group Baird & Co.

The biggest hurdle, he said, has been getting what the Bureau of Labor Statistics refers to as shelter costs to come down. Those costs come in two main categories: rent and homeownership, called owners-equivalent rent.

Both categories have now spent months defying forecasts of a meaningful slowdown in price growth, remaining above 6% on a 12-month basis in January.

In February, shelter costs once again proved stubbornly high, climbing 5.7%.

"The components we thought would have reduced, especially shelter, which comprises the bulk of CPI — it’s a gigantic weight in the composition of the index — we thought would have dropped further," Antonelli said.

On Monday, the real estate group Redfin reported rents climbed 2.2% year over year, to $1,981 in February. That's the largest gain since January 2023. Month over month, it increased 0.9%.

Some of the data about the strength of the economy going forward remains conflicting. Last week's employment report showed that while the economy continued to add jobs at a healthy clip, the unemployment rate ticked upward.

Other factors remain at work, too. Supply-chain issues, particularly related to trouble in the Red Sea, may start showing up again in the form of higher goods prices, analysts with Citibank told clients in a note Monday.

“We do not expect inflation data over the coming months will be an overwhelming contrast to strong January data,” the Citi analysts wrote.

Antonelli said the market and the economy remain healthy — so much so that instead of the "soft landing" hoped for by the Fed, in which inflation continues to fall without a significant increase in unemployment, consumers are now looking at a "no landing" scenario.

That is not necessarily a bad thing. It just means that above-forecast inflation is most likely here to stay for some time.

"A 'soft landing' implies we are near some kind of ground, but we’ve bounced into the 'no landing' category," Antonelli said. "We're in a situation where we have good demographics, a vibrant economy, a tailwind with [artificial intelligence], the housing market is strong — all the things we see the economy now doing."

Workers, however, are barely keeping their heads above water, with wages having only marginally outpaced inflation. Today, inflation-adjusted weekly earnings total about $371, compared with $367 in the months just before the pandemic.

"It's like having your pocket picked and then seeing that a bill happened to fall out," said Mark Hamrick, senior economic analyst and Washington bureau chief for the financial group Bankrate. "You’re able to put it back in — but you’re not getting any restoration from the damage in purchasing power.”

For the Fed, the fact that it has raised interest rates without setting off an unemployment crisis means those rates are likely to remain high for some time as it sees greater risk from prices accelerating again compared with the threat of rapidly rising unemployment.

While traders are betting that the first interest rate cut of the post-pandemic period will arrive in June, a new Reuters survey found respondents now believe there will be fewer rate cuts this year than had been forecast.

In his recent testimony to Congress, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said the first rate cut of the post-pandemic period would most likely come this year — but he could not say when, given the ongoing inflationary pressures.

Other forecasters see a global economic situation that could keep the U.S. at 3% inflation indefinitely. David Andolfatto, a former Fed official who now chairs the University of Miami business school's economics department, said ongoing geopolitical turmoil and demand for defense spending will most likely keep the pace of price growth firm.

Ongoing federal budget deficits — a phenomenon that both political parties have signaled little willingness to resolve — are not helping, either.

"These types of economies tend to run hot," Andolfatto said. "I just see fiscal pressures from either side, and getting inflation back down — compared with the previous decade, where we were undershooting — I just think that world is gone."

Source: nbcnews.com